This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1007 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, thanking our guest writers

Yves here. This short and important post is about regulatory forbearance, which in layperson terms means choosing to allow regulated parties to get aways with not complying with the rules, because mumble mumble. Here, a big reason for bank regulatory forbearance is to cover up losses, in the hope that at least some sick-looking loans will prove to be money good when the economy or sector recovers. This piece describes that even in a cooperative, wink and nod process, the accountants are more than a tad aggressive in presenting a prettied-up image.

By Edward J. Kane, Professor of Finance, Boston College. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Accountants portray themselves as truth-tellers, but especially when they work for a dangerously undercapitalized bank, their jobs are far more complicated than that. In INET Working Paper 136, I compare skilled bank accountants to master illusionists such as Siegfried and Roy. Much as these famed magicians made audiences think that they could make large wild animals disappear, some bank accountants enhance their income by convincing client banks that they have the power to make losses disappear. But in both kinds of illusion, items we no longer see have not actually vanished. They have been moved surreptitiously to places for which outsiders have no sightline.

This relocation process occurs under the cover of one or another cloaking device. The paper identifies some of the devices that bankers use to cloak losses. The simplest of these involves under-reserving for known or anticipated loan losses by deliberately overestimating distressed borrowers’ ability to repay.

The research reported on here develops and supports the related hypothesis that what looks like an energetic effort by bank regulators and self-regulatory organizations to control loss concealment is at least partly a sham. In practice, details of banking reforms are worked out between bankers and regulators and confirmed by elected politicians. If successive banking reforms were not shaped to serve these parties’ joint interests, the wave after wave of counterfeit reform we observe would not be allowed to work so poorly or would at least be designed to work better for a longer time.

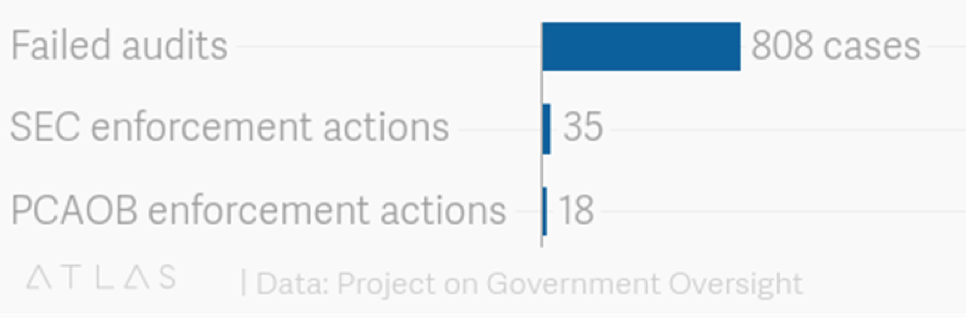

My INET paper develops circumstantial evidence that supports the narrower hypothesis that politicians and policymakers find it is in their joint interest to tolerate substantial loopholes in bank accounting rules and standards. Negotiating and enacting opportunities to hide bank losses serves the interests of politicians, bankers, and incumbent regulators alike, but does so in different and in subtle ways. Accountants know that this system could not continue to function unless regulatory forbearance extended to their work as well. Figure 1 shows that the Securities and Exchange Commission disciplined accounting firms in less than four and a half percent of the cases its investigators uncovered. The accounting industry’s self-regulatory arm –The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board—imposed penalties at roughly half that rate.

Financial stability is an explicit goal of modern central banking and every bank and central bank regards secrecy as an important tool. Elected and appointed officials make informational evasions and falsehoods available to insolvent bankers because their evasions and falsehoods help officials to minimize their own exposure to blame and let them block and reshape the flow of adverse information at critical times. Although many forms of government secrecy are openly embraced, loss concealment is an unacknowledged instrument. Its purpose is to discourage disorderly bank runs in periods of financial stress. Especially in the short run, authorities find it politically and reputationally less dangerous to suppress adverse accounting information than handing the taxpaying public an immediate and accurate accounting of the bill that is coming their way.

In view of the severity of the Covid-19 crisis, regulators have decided to be less sneaky this time around. They have openly advised examiners and bank accountants to help troubled bankers to make loan losses disappear from their firms’ balance sheets and income statements. Allowing too-big-to-fail banks to misrepresent the depth of their accumulating losses is one leg of a conscious strategy through which bankers and regulators hope to lessen the threat of destructive Covid-driven systemic runs on the world’s banking systems. The second leg of the strategy rests on another fiction. Prudential regulators around the world are telling us that they can and do maintain financial stability by assuring the adequacy of what they call “bank capital.” But the statistical measures of bank capital on which regulators focus their efforts are nothing more than repurposed variants of a bank’s accounting net worth. With accountants able to conceal the impact of losses on accounting net worth, until and unless unsophisticated household depositors begin to fear that a bank may have let itself become deeply insolvent, the effectiveness of this control framework is being badly oversold.

In an industry crisis, this disposition toward supervisory informational deception and regulatory forbearance creates a risk-hungry herd of what economists now characterize as “zombie” banks. A zombie bank is a financial institution whose economic net worth is less than zero, but which can continue to operate because its ability to repay its debts is credibly backed up by a combination of implicit and explicit government credit support.

A zombie’s managers can not only keep themselves in business, they can grow their assets massively. But they can only do this when and as long as creditors are confident that government officials somewhere are ready and able to force their country’s taxpayers to make good on any missed payments. Almost no matter what interest rate a central bank or deposit insurer charges a zombie for its emergency credit support, the funding is almost always being offered at what is de facto a subsidized rate. In providing this subsidy, taxpayers accept a poorly compensated equity stake in the survival of the zombie enterprise.

To treat taxpayers more fairly, it would be appropriate for authorities to presume that each and every bank threatened by a run is almost certainly undercapitalized. Because it is costly all around for depositors to close their accounts suddenly, it is reasonable to assume that at least the early wave of “runners” have seen something concrete to worry about. This line of thinking leads me to recommend that authorities should be required either to freeze the positions of uninsured creditors whenever a bank suffers a statutorily defined “abrupt and rapid shrinkage” in its liabilities or, in the event of a bank’s sudden failure, to have the right to reverse transactions by uninsured creditors whose ability to exit would not have been possible in the absence of the emergency funding supplied by the central bank or other government agency.

This blog seeks to explain that teams of financial illusionists stand ready to conceal developing losses and other forms of dishonest behavior. Bankers’ and regulators’ capacities for deception make it self-defeating for taxpayers to accept a social contract that turns on accounting measures of capital and self-administered stress tests. I believe that the world’s system for penalizing accounting misrepresentation at government-insured financial institutions desperately needs to include the possibility of imposing criminal as well as civil penalties on violators. The processes through which bankers extract benefits from the safety net closely resemble those of embezzlement and the rewards bankers garner usually rise to the level of grand larceny. The difference between street crime and safety-net abuse lies mainly in the class and clout of the criminal and the subtlety of the crime.

FIGURE 1 BIG 4 ACCOUNTING FIRMS WERE PUNISHED FOR ONLY A FRACTION OF FAILED AUDITS BETWEEN 2009 AND 2017Source: ATLAS Data Project on Government Oversight

Like Trump the bank’s biggest assets are the lies they tell.

The Sunday NYT story about Trump’s taxes tacitly begs the question of where is the money Trump keeps losing coming from? What if the Trump organization is just a big international money laundry?

Tom Burgis’ article in the DailyBeast stimulated one possible answer. Trump’s business is about losing money to launder it. Trump lives like a billionaire on other people’s money. The losses allow big tax deductions, and businesses grossly overcharge and take a cut before passing it back nicely cleaned. Who pays $70K/year for haircuts? I pay like $150/year.

*Sigh*

There is a big difference between tax losses and cash losses.

And Trump (save maybe for his casinos) can’t be in the money laundering business unless his buyers pay him with huge bags of cash. Payments for real estate go through banks. Getting dirty money INTO the banking system is what money laundering amounts to, not what you do with it once you’ve gotten it into a bank. That is why banks and not real estate and art owners and diamond dealers (to list a few places to park money) are subject to “know your customer” rules and required to make anti-money laundering checks.

As for the hand-wringing that Trump has $300 million of debt maturing in 3 years, he’s underleveraged for a guy in real estate. He had plenty of borrowing capacity to pay off those loans with new loans, particularly in this super low interest rate environment where banks are falling all over themselves to lend.

Yves, thanks for the education. It just seems like losing on such a scale over such a long period of time seems unsustainable unless there is something illegal going on that actually generates profits using Trump as a passthrough.

I agree that the pending $300M loan is likely to be a nothing burger, however, if the Deutschebank scandal gets worse and Trump bubbles to the surface, would you invest in Trump?

Keep in mind, this is a tax statement. The goal of the tax statement is to pay as little tax as possible. The goal is not to show a accurate picture of your financial well being, to the contrary.

That means you try to inflate the value of losses, and pull them forward in time. On the other hand, you try to undercount and postpone increases in value of your properties. Unless there temporary opportunities in the tax code, then suddenly your properties gain or lose value right in that window.

If you are not selling, there is a wide leeway in the proper valuation of properties. That is also related to all those loans. If you want cash for whatever, purpose, you sell a stake in a property you own. But that would lead to an unambiguous valuation of the entire property. If you take out a mortgage, you only have to show enough valuation to act as security.

Another part of personal consumption – the Trump family lifestyle counts, as far as the tax accounts can push it, as a business expense. They live on company properties, surrounding by companies employees, even their hair gets cut as a business expense.

At some point, you reach a tax accounting nirvana of pure poverty. Everything you own is decreasing in value, all the cash you get in has to be spent on business expenses, all those projects are sad failures that don’t raise the value of anything, you never get to spend anything on personal pleasure, and whatever you have left goes to charity.

The answer to “how banks hide losses” is really simple – “any way they can”.

Although the easiest is usually preferred, which means as the post says messing up with the unrealised losses.

TBH, there’s no good way to deal with the losses – even realised, which you can always turn into un-realised by dragging out the settlement and in the meanwhile having various estimates on the ultimate recovery.

As the banks are now, they are fundamentally under-capitalised – IMO anything below 20% for a bank that does uncollateralised lending is too low.

On the other hand, there’s a relatively fine line between too much capitalisation – say 100% (full-reserve banking) would mean that settlement risk could bring down the whole system (cf current payment systems and their behaviour, which are not 100% reserve, but do operate on credit). Credit (and thus leverage) is important to economy, but it’s hard to say how much. No credit is bad, but the situation where we have way too much credit right now is almost as bad.

“forbearance” in first graf. Freudian cite of Ed Bernays? :)

They teach auditors that frauds and other hidden things usually comes to light when their has been a change of personell at the client. The one stepping in goes through as much as he/she can to be able to blame the predecessor for losses, it is similar to the due diligence that investors do. But it can be dangerous for the new one, the one who left might still have friends in the organisation and thus the new one might find him/her-self with having created a set of enemies by going after their friend in such a way.

What the people training auditors sometimes forget to explicitly tell trainee auditors is that it happens that after a change of auditor then the new auditor might uncover something hidden. (Wirecard might be one such example)

Cleaning up big enterprises might be seen as a Herculean task, possibly even worse than that. If bad behaviour has been going on for years then almost all of senior management and senior executives will fight the effort to clean it up – mainly because if the mess is cleaned up then managers and executives will find themselves to be in big trouble.

If the organisations were to be treated as criminal enterprises and plea bargains were to be used then the lower ranks would implicate senior managers and executives. I am generally not a fan of plea bargains, however, I believe that it might be the only way to deal with large and/or powerful organisations. Go after them in almost any other way and the lower ranks will keep quiet – the lower ranks have nothing to gain by talking and everything to lose if they speak. They might even be rewarded for keeping quiet.

Audits, both internal and external, are in my opinion generally quite worthless when done of bigger companies. The auditors will look for the pennies but the pounds will not look out for themselves (paraphrasing from https://wordhistories.net/2018/01/29/look-after-pennies/)

” The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry” (2005). Regular NC readers are probably familiar with Bill Black’s work.

The lessons learned from the S&L melt down seem to be…?

Um, that after the S&L Crisis the Bush Justice Department put >1,000 white collar bankers in jail?

Do I win a prize for pointing out that Obama made sure that number was zero after 2009?

Here’s Matt Taibbi on Bill Moyers giving chapter and verse, start at 2:00.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sdhX92ZttnU

As one of the prosecutors stated : “HSBC broke basically every law on the books and they did business with every kind of criminal you can imagine“.

The outcome? A fine equal to a few days’ revenue for the bank. As Taibbi says, the precedent basically created a second class of citizens who are immune from prosecution under the law: bankers.

But I forgot, “There were no scandals under Obama”. LOL

And no wonder the WaPo and NYT are currently working hard to cancel Taibbi.

This still promotes the pervasive myth that “taxpayers” bear the losses… For monetary sovereigns (fiat money, floating exchange rates) taxpayers don’t provision the government, no matter how great are the programs that cover up these losses. Slipping the myth in there is a commonplace, but it needs to be called out.

It is no myth that responsibility for covering a zombie bank’s current and future losses has to be absorbed by someone. As long as an insolvent bank is allowed to continue to operate and take new risks, its net loss exposure passes onto the government safety net. Once a bank is seen as too big and too complex for government liquidators to handle, the government’s option to close or take over the bank is not going to be exercised no matter what new losses it rings up. This is what it means for a bank to be too big to fail. Congress does not need to appropriate government funds, but the zombie is playing on the taxpayer’s dime as long as it remains insolvent. Capital forbearance means that the government is not fully enforcing solvency requirements. To balance the bank’s economic accounts, the government must be assigned an unbooked and unrecognized equity position. The bank may pay interest on explicit government loans, but it pays no formal dividend to the government on its equity stake. In this case, stockholders still enjoy a claim of future earnings if the bank ever manages to recover. This encourages long-shot loans and investments that may themselves have negative present value. Hence, the value of stockholder equity in an operating zombie bank resembles a lottery ticket, whose value the zombie’s managers can optimize.

The problem is we insist on mixing what should be risk-free deposits with what are inherently at-risk deposits – for the sake of “efficiency”, I suppose.

But when it comes to finance, ethics should be paramount, not the supposed “efficiency” of sticking with an obsolete, inherently unjust Gold Standard banking model.

There are a lot of “weasel” words in this article:–

E.g., ” supervisory informational deception” instead of lying, cheating, defrauding, stealing

“regulatory forbearance” instead of lying, defrauding, misrepresenting

“financial illusionists” instead of liars, corrupters, criminals, crooks, felons, lawbreakers, evildoers, malefactors.

Wow! Just Wow!

You call them weasel words. But I call them specific forms of cheating defrauding, lying, and stealing.

I like Edward Kane’s writing style. Very straightforward. I don’t like his remedies. Too straightforward. If we have all come to this end together (which we have) we should not have the luxury of finger pointing. The only thing that stops recrimination of this sort is a gold standard and that’s the biggest oxymoron of all. I’m not crazy about the banksters, but I’m far less crazy about Wall Streeters and even less crazy – in fact close to cold hard rationality – about our completely irresponsible grift-and-graft-Congress. It’s a pass the buck congress in a pass the buck nation in a world that has come to the end of places to pass the buck. The answer, imo, is not draconian accountability at all. It’s just the opposite. The answer is a green new economy financed by direct spending at every turn and twist – with generosity for the environment, the planet and all its creatures. Even Mr. Kane himself. Because, duh: money only ever has meaning by the way it is spent.

The author is rightfully focused on banks’ pandemic-related loan losses. However, it is noteworthy that high numbers of zombie companies substantially pre-dated the emergence of the Covid epidemic. Questions also exist regarding the possibility of losses in off-balance sheet derivatives, structured investment vehicles, direct or indirect speculative trading, and various operating risks. Besides the author’s suggestion of imposing criminal as well as civil penalties on willful violators, it is time to fundamentally restructure the nation’s monetary and financial system to eliminate safety-net abuses, protect the nation’s depository and payments system, increase lending for productive purposes rather than gains from financial engineering and speculation, and balance risk and rewards aligned with constructive social values. Such measures would moot some current arguments regarding capital adequacy.

“A rolling loan gathers no loss”

I prefer to say its accounting value “shows” not the loss it gathers.