Foreword

The Sana’a Center’s Yemen Annual Review 2019 is a comprehensive survey and analysis of the year’s events related to Yemen. In the Executive Summary below you will find overviews of each section and tables with their corresponding subsections, each hyperlinked to allow for easy navigation throughout the Review document. To return to the summaries and contents lists, simply click ‘back’ on your browser

The Sana’a Center’s Yemen Annual Review 2019 is a comprehensive survey and analysis of the year’s events related to Yemen. In the Executive Summary below you will find overviews of each section and tables with their corresponding subsections, each hyperlinked to allow for easy navigation throughout the Review document. To return to the summaries and contents lists, simply click ‘back’ on your browser

Executive Summary

Coalition Collapse and Rebirth

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates led a regional military intervention into Yemen in March 2015 on behalf of the internationally recognized Yemeni government, which had fled the capital, Sana’a, following a takeover by the armed Houthi movement and its allies. At the time, Riyadh claimed that the coalition it headed would need only weeks to drive Houthi forces back and restore the Yemeni government to power – fast forward five years and the war is still raging. What 2019 made clear is that the conflict is an unwinnable quagmire, while the means to end it remain elusive.

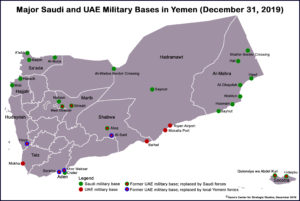

Major new complications emerged in 2019 when disunity within the anti-Houthi ranks burst to the fore, with the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and forces loyal to Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi turning their guns on each other in August. The STC – which harbors deep-seated grievances against the central government and seeks to revive an independent state in south Yemen – pushed pro-Hadi forces out of the interim capital of Aden in what amounted to a coup d’etat, and fighting quickly spread to other southern governorates. Similar violence had also broken out in Aden between the two sides in January 2018, but then the STC was reined in by its primary backer, the United Arab Emirates (UAE). However, 2019 saw the UAE reassess its involvement in the conflict and eventually withdraw most of its forces from the country. Abu Dhabi’s decision to pull out of most of Yemen allowed it to distance itself from the STC’s actions and set the stage for Saudi Arabia to eventually assume sole leadership of the anti-Houthi coalition.

With fighting threatening to irrevocably split the coalition and open up a new front in a civil war, Saudi Arabia called for an urgent dialogue in Jeddah between the Hadi government and the STC. After gaining Abu Dhabi’s buy-in for the talks, Saudi Arabia was able to broker a deal between the Yemeni parties that, on paper, would unite them under Riyadh’s ultimate authority. The accord signed in November, which became known as the Riyadh Agreement, laid out an overly optimistic timeline for the STC to be absorbed militarily and politically into the Yemeni government. On the military front, all security forces would come under overall Saudi command, enshrining the UAE’s pullout from Yemen by making previously Emirati-backed groups, such as the STC, now dependent on Riyadh for support and financing. On the political front, all major government decisions would be subordinated to Saudi Arabia. However, since the signing ceremony, every implementation benchmark has been missed, save for the return of some government ministers to Aden. Thus, it remains to be seen whether Saudi Arabia can truly force two groups who harbor deep distrust and enmity toward one another to implement a deal that seeks to reconstitute a more effective and accountable Yemeni government and stabilize southern Yemen.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Coalition Collapse and Rebirth’ including:

- Khalid bin Salman Takes Saudi Lead on Yemen

- Shock UAE Drawdown Sets the Stage for Coalition Turmoil

- The Anti-Houthi Coalition Implodes

- The Road to the Riyadh Agreement

Saudis, Houthis Enter Talks as Drone Warfare Ups the Ante

The armed Houthi movement increasingly demonstrated its lethal capabilities with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) – otherwise known as drones – and guided missiles in 2019. The group escalated targeted strikes both in Yemen and across the northern border into Saudi Arabia, with two game-changing attacks last year being claimed by the Houthis.

An August 1 attack in Aden killed influential Security Belt forces commander Muneer al-Mashali, better known as Abu al-Yamama, and 35 other soldiers, setting flame to simmering tension in the interim capital and the stage for the STC’s coup against the Yemeni government that month. Houthi forces claimed they had used a drone and medium-range ballistic missile to strike the camp.

The next month, the Houthis claimed credit for the September 14 strikes on a Saudi Aramco oil facility in Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia. This temporarily sent global oil prices skyrocketing and cast a pall in the lead-up to an initial public offering for shares in Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil producer and most profitable company in the world, with an estimated worth of well over a trillion dollars. Riyadh, Washington and European allies blamed Iran for the attacks, though the immediate result was that Saudi Arabia began exploring behind-the-scenes deescalation talks with both Iran and Houthis, with the preservation of the Saudi economy being Riyadh’s primary motivation.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Saudis, Houthis Enter Talks as Drone Warfare Ups the Ante’ including:

- The Year of the Drones

- Aramco Attack Exposes Vulnerability of Saudi Economy, Cease-Fire Ensues

- The Saudi-Houthi Backchannel

- Deescalation Loses Momentum as Year Ends

Life Under the Houthis: A Descent into the Dark Ages

When the armed Houthi movement and forces loyal to former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh took over Sana’a and much of northern Yemen in 2014, maintaining the alliance between them demanded compromises on both sides. Though positions of political, security and economic clout in their governing apparatus were hotly contested, their common enemies – the Yemeni government and the Saudi- and UAE-led coalition – created the impetus to make deals and parse appointments. This process limited each’s ability to pursue their respective agendas, with Saleh’s secular-minded General People’s Congress party generally checking the Houthis’ ability to institutionalize their hardline religious ideology through the mechanisms of state.

In late 2017, the Houthi-Saleh alliance dissolved in spectacular violence, ending – after days of street battles – with Houthi fighters parading the former president’s bullet-ridden corpse before the cameras. In the two years since, Houthi authorities have used their uncontested rule behind the frontlines to increasingly build a mafia statelet in their own theocratic, totalitarian image. In 2019, this process continued to accelerate and involved further remaking school curriculums to disempower free-thought, facilitate child conscription into Houthi forces and inculcate the Zaidi Shia doctrine. The movement mandated public servants’ attendance at regular indoctrination classes and at a swathe of new official religious celebrations – the latter of which were financed through ‘donations’ solicited from businesses and individuals that often amounted to officially-sanctioned extortion and protection rackets.

The iron grip with which Houthi security and intelligence forces control northern Yemen – home to the country’s largest population centers – has allowed them to impose new taxes and fees at will, bully businesses and manipulate markets to fund their war effort; extreme examples of the latter being the manufactured fuel shortages in the spring and autumn that created massive cash windfalls for Houthi-affiliated black market fuel vendors.

Houthi security forces have eradicated dissent in the public sphere, having shut down all independent media outlets and continued the imprisonment of journalists and political activists, while the persecution of religious minorities also persisted through 2019 in northern Yemen. New regulations the Houthi authorities brought in also further choked the independence of international NGOs and their ability to operate, with aid groups already facing widespread harassment, theft, threats and restrictions on their operations before the year began.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Life Under the Houthis: A Descent into the Dark Ages’ including:

- Bringing Government and Security Apparatuses into the Houthi Fold

- Religious Indoctrination

- Continuing Crackdown on Dissent

Political Developments: Fragmentation and the Struggle for Legitimacy

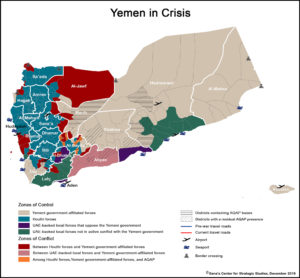

While frontlines shifted little, territorial and political fragmentation continued in Yemen throughout 2019. Houthi-held areas were relatively stable, though life under the “iron fist” was suffocating for many as the armed Houthi movement tightened its grip over Yemen’s largest population centers in the country’s north. On the other hand, several areas controlled by anti-Houthi forces suffered from instability and local infighting, with different groups competing for power. The internationally recognized government, nominally controlling these areas, largely remained in exile throughout 2019.

Continuing a trend from the previous year, the government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi retained limited leverage on the ground and its authority was increasingly challenged. In an attempt to reaffirm some legitimacy in 2019, Hadi’s backer Saudi Arabia put considerable effort into holding a parliamentary session in territory nominally held by the government. It was the first session held by the government since the beginning of the war. Houthi authorities had repeatedly held parliamentary sessions in their areas in the past, and did so again in 2019. However, both failed to garner a legal quorum of MPs in the House of Representatives, which has been split due to the war.

The legislative session of MPs loyal to the Hadi government took place in Sayoun, northern Hadramawt governorate. Challenges posed by the separatist Southern Transitional Council (STC) prevented the session from being held in the government’s temporary capital, Aden. Despite the lack of a legal quorum, it was the first time that a Yemeni legislative body had endorsed the Saudi-led military intervention. Divisions within the anti-Houthi alliance were one factor preventing a quorum on the government side, with STC-aligned MPs not attending the session.

Greater unity appeared to be on the horizon after the signing of the Riyadh Agreement, crafted to unite anti-Houthi forces under a Saudi umbrella. However, as of January 2020, the implementation appeared to be indefinitely delayed, and the fragmentation of the country was becoming ever more entrenched.

Local power struggles in Yemen often have been reinforced by foreign powers, with Taiz a case in point. While the city continued to suffer from a partial siege imposed by the armed Houthi movement, competition among anti-Houthi forces, namely the Islah party and its opponents, led to further instability in the governorate and increased the risk of a new advance by Houthi forces. The conflict within the anti-Houthi camp was reinforced by regional rivalries, with Qatar funding a new military camp established by Islah-affiliated forces – a move clearly intended to antagonize the Saudi- and UAE-led coalition.

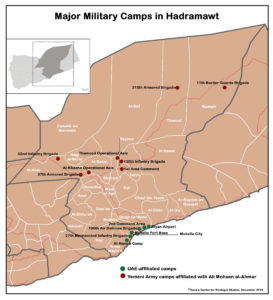

In other areas, de facto federalism continued with local actors pushing for more autonomy from any outside authorities. Marib remained relatively stable under the rule of its powerful governor in an alliance with tribes and the Islah party. Yemen’s largest governorate in terms of area, Hadramawt, also became more vocal in articulating a Hadrami identity and expressing its desire for local autonomy. This Hadrami particularism has proven to be stronger than divisions within the governorate. The south of Hadramawt around the port city of Mukalla is controlled by UAE-backed forces, while Saudi-backed forces, including Islah-affiliated troops, dominate the north. Hadramawt stayed neutral vis-à-vis the conflict in the south between the UAE-backed STC and Saudi-backed government forces in 2019.

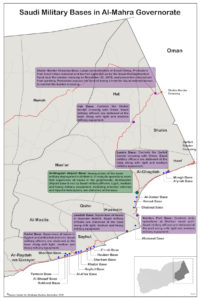

Likewise, the separatist STC was unable to garner significant support in Al-Mahra and Socotra during its attempted takeover of southern Yemen in the fall of 2019. The desire for local autonomy is historically stronger than for southern secession, as Yemen’s easternmost governorate once formed a sultanate together with the Socotra archipelago. Meanwhile, both Al-Mahra and Socotra witnessed protests against the presence of coalition powers. In Socotra, an Emirati attempt to install a local proxy force was met with local opposition. In Al-Mahra, a protest movement against Saudi military expansion has, since 2018, increasingly gained the support of neighboring Oman, an unusual development given Muscat’s traditional politics of non-interference.

Matters seemed to take an even more complicated turn in southern Yemen with the establishment of the National Salvation Council, a collective of southern factions opposing the Saudi- and UAE-led military coalition. Among the southern opposition figures to call for the council in September was a prominent representative of the anti-Saudi movement in Al-Mahra. However, its relevance on the ground has yet to be demonstrated.

As southern Yemen was riven by power struggles and the north was suffocating under the tightening Houthi grip, a new actor quietly began establishing his own statelet on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast. Tariq Saleh had emerged in 2018 as the leader of the battle for the Houthi-controlled port city of Hudaydah. After the offensive was halted with the signing of the Stockholm Agreement in late 2018, the nephew of the late ex-president Ali Abdullah Saleh began to consolidate his power along the western coastline. Enjoying unequivocal support both from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Tariq Saleh has become a sort of gatekeeper in the area in terms of both military and financial support.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Political Developments: Fragmentation and the Struggle for Legitimacy’ including:

- Competing Parliaments

- De Facto Federalism in Government-Held Areas: Marib and Hadramawt

- Taiz: A Showcase of Power Struggles and Shifting Alliances

- Al-Mahra and Socotra: Pushing Back Against Saudi and Emirati Influence

- Tariq Saleh’s Statelet by the Red Sea

Frontlines and Security

Frontlines nationwide shifted little in 2019, but the armed Houthi movement ended the year with an upper hand militarily, primarily by maintaining its cohesion while factions within the anti-Houthi coalition turned on each other. Houthi forces continue to control most of Yemen’s largest population centers, including the capital, Sana’a, and its fighters also managed to reverse 2018 gains by coalition forces in northern Yemen near the border with Saudi Arabia. It was a significant change of fortune from the year before, when the anti-Houthi coalition was exerting pressure on several fronts, most notably along the Red Sea Coast in an offensive toward the port city of Hudaydah.

Apart from the northern front, the only other significant shifting of primary frontlines centered around Al-Dhalea governorate. In Hudaydah, the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement that froze frontlines around the port city held throughout the year. Zones of control on other fronts, most notably in Taiz and Marib governorates, also remained unchanged, despite occasional bouts of heavy fighting.

Throughout the war, the Saudi- and Emirati-led coalition’s modern air force has dominated from the sky, and its forces on the ground are better armed and trained, but the Houthis were able to maintain countervailing pressure by stepping up their use of drones and missile strikes in 2019 inside Yemen and across the border into Saudi Arabia. It was an effective use of an asymmetric warfare tactic, and it ultimately contributed to Riyadh accepting a partial cease-fire offer by the Houthis in September. That, in turn, was a catalyst for direct talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi movement.

On the counterterrorism front, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula found itself weaker than ever in 2019, focused on a four-front war against various Yemeni foes. One of these enemies was the Yemeni affiliate of the Islamic State group, with the two rival jihadi groups carrying out more operations against one another than any other entity in 2019. Simultaneously, while the United States under the Trump administration has become more opaque about reporting its counterterrorism operations in Yemen, data suggests that American drone and air strikes in the country continued to decline dramatically from their 2017 peak.

The most dramatic military advances and retreats of 2019 occurred when anti-Houthi forces turned their weapons against each other in southern Yemen in August and September. Though Saudi Arabia ultimately patched over the factions’ differences with the Riyadh Agreement, it remained unclear at the end of the year whether troops aligned with the Yemeni government and other anti-Houthi forces would be capable of overcoming their mutual distrust and eventually mount coordinated offensives against Houthi-controlled areas. The prospect of an all-out military victory against the armed Houthi movement – a daunting task even when the Saudi- and Emirati-led coalition entered the war in 2015 – appeared as remote as ever as 2020 began.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Frontlines and Security’ including:

- Most Important Anti-Houthi Ground Forces

- The Northern Front

- Al-Dhalea Front

- Jihadis and Counterterrorism

Economic Warfare: Government and Houthi Struggle for Control Deepens

The confrontation between the Yemeni government and Houthi authorities’ for regulatory control over fuel imports, monetary policy, commercial banks, money exchangers and other aspects of the economy continued to escalate in 2019. Each side sought to exploit its specific leverage points in this struggle: the Yemeni government, its Economic Committee and the Aden-based Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) hold international legitimacy and the accompanying connections to international financial markets, while Houthi authorities and the Sana’a-based CBY branch have remit over the country’s largest financial hubs and commercial markets. Meanwhile, ordinary Yemenis continued paying the price of this economic warfare through commodity shortages, inflation, a fragmenting national currency system, unemployment and lost earnings.

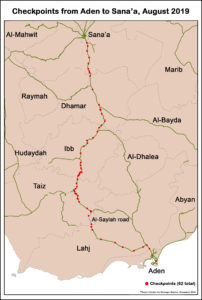

For instance, Yemeni government attempts to impose regulations and tariffs on fuel imports to Houthi-held Hudaydah port, and Houthi attempts to thwart such measures and protect their business interests, led to widespread fuel shortages in the spring and autumn as fuel tankers idled offshore waiting to unload. UN intervention in the fall led to a tacit, if tenuous, cease-fire in this battle: both parties agreed to deposit fuel import tariffs at the Hudaydah central bank branch and use the funds to pay public servants in the governorate; none were paid by year’s end, however, over a dispute whether to include those hired after the Houthi takeover in 2014.

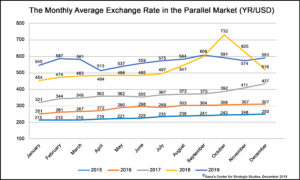

Yemeni banks and money exchange companies were another battleground. The Aden central bank has attempted to stabilize the Yemeni rial exchange rate and restart formal financial cycles through providing traders import financing for basic commodities at preferential rates. Simultaneously, however, requirements that letters of credit be paid for in cash through commercial banks threatened to draw liquidity out of Houthi-held areas and undermine Houthi-linked importers; the Sana’a-based authorities thus prohibited compliance with the government’s decrees and deployed strongarm tactics against bankers and traders.

Economic brinkmanship hit a dangerous new precipice by year’s end when the Houthi authorities in Sana’a banned the use of currency notes printed by the Aden central bank since 2016. Black market currency trading and currency smuggling flourished as exchange rates began to diverge dramatically between Sana’a and Aden. This domestic currency destabilization comes as yet another threat looms; the US$2 billion deposit Saudi Arabia provided the Aden central bank in 2018 to finance imports is expected to be exhausted before the end of the first quarter of 2020. Without new foreign currency reserves the Yemeni rial will almost certainly plummet in value, which would leave vast swathes of the population unable to purchase basic necessities and at risk of famine.

Efforts to reunify the CBY – which is fragmented not just between Sana’a and Aden, but also divided within Yemeni government-held areas as well – largely floundered in 2019; government efforts to combat corruption appeared on a collision course with big business interests; and the disused FSO SAFER oil terminal offshore of Hudaydah governorate continued to threaten environmental disaster as the warring parties bickered about what to do with the million-plus barrels of crude oil aboard. The ongoing financial crisis in Lebanon and the resultant restriction on withdrawals also left many Yemeni banks and businesses unable to access their correspondent accounts with Lebanese banks.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Economic Warfare: Government and Houthi Struggle for Control Deepens’ including:

- International Legitimacy vs. Domestic Market Dominance

- Fuel Impasse Leads to UN Special Envoy’s Mediation

- Battle for Control Over Yemeni Banks and Money Exchangers

- Yemeni Rial and Government Food Import Mechanism Under Threat

- The Struggle to Rejoin a Divided Central Bank

- Favoritism, Currency Shenanigans and Market Monopolies

- FSO SAFER Environmental Threat Rises

Humanitarian and Human Rights

War-exhausted Yemenis found little respite in 2019 as they coped with broken education and health systems, water and fuel shortages prompted by warring parties’ strategy of weaponizing the economy, and insecurity that permeated all aspects of home and community life. Actions on the ground exacerbated the dire humanitarian situation, including Arab coalition airstrikes and Houthi-planted landmines, and the number of people displaced by the war kept growing. Warring parties continued to violate international humanitarian law by attacking schools, hospitals, and water and sanitation systems, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported in December. Cholera remained widespread at the close of 2019, and only half of all health facilities were fully functional. Humanitarian aid agencies — frustrated by restricted access to people in need, harassment and deadbeat donors — struggled to keep up, but found themselves scaling back instead.

Salary suspensions continued to plague public-sector employees in Houthi-controlled areas. As the war dragged on, even the most skillful juggling of family finances could stretch the devalued rial only so far, and parents’ struggle to pay for food, water and petrol turned other necessities — bus fares, school and university fees, school uniforms and supplies — into luxuries no longer in reach. Some students, as well as parents and teachers, also feared schools were simply too unsafe to attend, according to key studies and NGO reports in 2019 that highlighted the damage to Yemeni youths’ future caused by boys dropping out of school to work odd jobs or join fighting forces, and girls being kept home or married off early. In Houthi areas, teachers reported being pressed to indoctrinate students into Houthi ideology and cooperate in conscripting children.

The Houthi authority’s crackdown on dissent and differing viewpoints continued in areas under its control in 2019, visible in its detentions and trials of journalists, activists and religious minorities. The Yemeni Journalists Syndicate noted serious press freedom violations by all parties, including arbitrary detentions, assaults, threats and work bans, and said Houthi authorities opened a trial in December for 10 journalists allegedly tortured and detained since 2015. The Syndicate, however, noted a significant drop in the number of reported violations committed by all sides in 2019 compared to 2018, and in the number of journalists killed. The decline, however, appeared to be more related to the repressive and hostile work environment having pushed journalists out of the field than any security improvements.

In September 2019, the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen (GEE), a UN-appointed investigative panel, reported on an array of violations by the Houthis, the internationally backed Yemeni government, Arab coalition member states and various fighting forces on the ground. It found, for the second year running, that parties to the conflict may have committed war crimes amid an environment defined by lack of accountability. It also turned over a confidential list of names to consider for future prosecution. Among acts the GEE said may amount to war crimes were murder, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, sexual violence including rape, torture and child recruitment. It noted the security of women and girls had deteriorated since the outbreak of the war, and said there were grounds to believe all parties to the conflict had committed gender-based violence in acts that may amount to war crimes. The report also highlighted the precarious position of refugees, migrants and minorities, and it said economic policies of both the Houthi authorities and the internationally recognized Yemeni government – particularly those impacting the value of the Yemeni rial – had exacerbated the crisis. The experts reported that all warring parties had impeded humanitarian access, an increasing frustration throughout the conflict for aid agencies.

During 2019, these access challenges were brought into sharp focus in Houthi-held areas, with restrictions on aid organizations soaring over the course of the year. In tandem, the Houthis’ tight grip on government ministries and institutions has raised questions about accountability in the use of aid funds, while the movement has sought to control humanitarian response in the north through its own aid coordination body. The UN World Food Programme (WFP), frustrated by aid diversion in Houthi-controlled areas, announced a partial suspension of operations in June 2019. While the suspension has since been lifted, talks between the WFP and Houthi authorities regarding mechanisms to ensure aid reaches those in need remain ongoing. Toward the close of the year, humanitarian actors sought to exert pressure on the Houthi authorities to improve the operating environment – the implicit threat being cuts to funding that millions of Yemenis rely upon.

Humanitarian actors also have found themselves under greater scrutiny. A Yemeni social media campaign probed the fate of billions of dollars in humanitarian aid since the outbreak of the war, while the UN found evidence supporting allegations of corruption at one of its own agencies in Sana’a. Underpinning these myriad challenges is a contradiction at the heart of the humanitarian response in Yemen: that the largest contributors to the aid pot are those states that are prolonging the suffering of the population through their military intervention in the Yemen conflict. Saudi Arabia and the UAE continue to restrict commercial and humanitarian access to the country and destroy infrastructure and agricultural land through airstrikes while bankrolling politicians and armed actors who perpetuate violence. After pledging more than a billion dollars at the beginning of 2019, the UN has spent much of the year hounding the coalition partners to pay up while shutting down programs due to underfunding. In its planning for 2020, OCHA spoke of narrowing its priorities to target far fewer people in need.

Humanitarian actors will face new obstacles in 2020, including increased fees because of a strict Houthi ban that took effect in December 2019 on the use of currency issued by the government-run Aden central bank. Aid agencies deliver much of their direct aid relief as cash transfers using currency issued by the Aden central bank, which is no longer permitted in Houthi-controlled northern areas where the majority of aid recipients are located. These same restrictions will also make it more expensive for Yemenis who left the north for work in government-controlled areas to send remittances to family back home. Combined with continued salary suspensions, the economic impact on families will almost certainly worsen as agencies cut back their programs.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments’ including:

- Looking Beyond the Numbers

- Aid Interference Comes into Sharp Focus

- Human Rights: Seeking Accountability in the Yemen Conflict

Yemen and the Region

Against the backdrop of escalating animosity between Washington and Tehran in 2019, the Yemen conflict caught international attention as part of the regional calculus around Iran. At the same time, Iran and the armed Houthi movement continued to strengthen their ties, a process that had gained pace over the course of the war. In 2019, Iran was the first country to officially accredit an ambassador representing the Houthi leadership in its capital, Tehran. While this enforced the reductionist view of the Houthis being a proxy of Iran in some circles, importantly the administration of US President Donald Trump had actually walked back from this narrative by the end of the year, saying that Tehran does not speak for the Houthi movement.

The Houthi-claimed attack against Saudi Aramco oil facilities in September could, indeed, be seen in the context of increasing tension between Iran and the US. According to a Sana’a Center source in contact with parts of the Houthi leadership, it was coordinated between Tehran and Sana’a. The Houthis claimed the attack while Tehran denied any role, yet the message to Riyadh — and by extension the US and Western allies — was apparent from both: if escalation continued, Saudi Arabia could be hit where it hurts. The strike also demonstrated the Houthis’ relevance as an actor to be considered in any efforts to achieve regional security. The armed Houthi movement in 2019 also continued to maintain ties with Hezbollah in Lebanon, another party in the “resistance” camp backed by Iran.

As 2019 progressed, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) increasingly looked for diplomatic paths to reduce imminent threats posed by Iran and its allies. The UAE, which previously had pushed for an aggressive policy confronting Iran, in July 2019 signed a document with Tehran on joint maritime security. This came shortly after the announced withdrawal of Emirati troops from Yemen and other indications of the UAE reassessing its relationship with Iran. In the wake of the Aramco attack and restrained response from the US, the Saudi faith in Washington as a guardian was shown wanting. Without it, and after more than four years of warfare against what Abu Dhabi and Riyadh had seen as Iranian encroachment on Yemen, the military path increasingly seemed exhausted. At the same time, other countries in the region such as Oman and Pakistan assumed intermediary roles in Riyadh’s secret talks with Houthi representatives and efforts to ratchet down tensions with Tehran.

By hosting Saudi-Houthi talks in 2019, Oman continued to play its traditional role as a mediator even though Muscat and Riyadh differed sharply on developments in Yemen’s Al-Mahra governorate. Muscat continued its support for a protest movement against Saudi military encroachment in the eastern governorate bordering Oman. There was also anecdotal evidence of a collaboration between Oman and Qatar, and possibly Iran, in supporting Yemeni groups and movements that acted against the interests of the Saudi- and UAE-led military coalition. Since being expelled from that coalition in 2017, Qatar has taken a different stance on the Yemen war, most visibly so in its media empire, as Qatari-funded TV channels shifted from supporting the military intervention to becoming a platform for its most outspoken critics.

In addition to the UAE, other minor partners also pulled back their involvement in the Yemen War in 2019. Sudan began to withdraw some of its troops from the anti-Houthi coalition, though the gradual pullout indicated that the move was happening with the consent of the UAE and Saudi Arabia, the most important financial supporters of Sudan’s ailing economy. Morocco, meanwhile, suspended its participation in the coalition, which had been marginal to begin with, at the start of 2019.

In 2020, the potential for open conflict between Iran and the US, and its respective allies, continues to loom over the Middle East. This was demonstrated just two days into the new decade with the US assassination of Iranian Major General Qassem Soleimani, who was responsible for organizing Iran’s military operations across the region, including with allied groups such as the armed Houthi movement.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Yemen and the Region’ including:

- All Eyes on Iran

- Pakistan: Driving Mediation Efforts Between Iran and Saudi Arabia

- Oman: Between Mediation and Meddling

- Qatar: Undermining the Coalition

- Sudan: Scaling Down Troop Deployment in Yemen

- Morocco: Exiting the Coalition

Yemen and the United Nations

The UN’s diplomatic achievements in Yemen were notable in 2019 for their absence; breakthroughs during the year took place outside the UN framework. While 2019 began with guarded optimism over the UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement, reached in December 2018 between the internationally recognized government and the armed Houthi movement. The accord contained three points: an immediate cease-fire in Hudaydah and mutual withdrawal of forces from the city and the nearby ports of Hudaydah, Saleef and Ras Issa; prisoner exchanges; and a statement of understanding on the city of Taiz. By year’s end none of the promises had been fully delivered.

Events on the ground in Yemen during the second half of 2019 pushed the already stalling UN efforts to implement the Stockholm Agreement further to the margins. Fighting in August between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) diverted attention to the need to prevent a new front opening in Yemen’s civil war. Deescalation efforts there were led by Saudi Arabia, culminating in the signing of the Riyadh Agreement in November.

The talks in Riyadh were driven by Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman, the younger brother of Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman; UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths welcomed the Saudi initiative, characterizing it as complementary to the UN-led efforts. Meanwhile, in late September, a backchannel opened for direct talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis to negotiate confidence-building measures outside any formal framework. These discussions remained ongoing at the end of the year and have already resulted in multiple prisoner releases. These conciliatory moves were characterized by both sides as attempts to fulfill the prisoner exchange aspect of the Stockholm Agreement, but they were negotiated outside the UN framework after multiple UN-led efforts to facilitate prisoner exchanges through the year had stalled.

There were various reasons for the lack of progress on the Stockholm Agreement. The text of the accord was left purposely vague to ensure buy-in from the warring parties, with the consequence that it was open to different interpretations. Also, it lacked a realistic timetable for implementation. The cease-fire in Hudaydah was implemented immediately – the agreement’s only clear success – but UN efforts on the redeployment of forces and what to do with port revenues repeatedly hit impasses as the year progressed. UN-led negotiations for a prisoner exchange ended in the spring without success, and there was little discernible effort to even begin talks for a deescalation in Taiz.

UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths spent much of 2019 engaged in shuttle diplomacy, between Sana’a and Riyadh in particular, along with visits to other regional and world capitals to meet with stakeholders in the Yemen conflict. But diplomacy veered off in a new direction after the STC ousted the Yemeni government from Aden in August in a violent coup. The two parties reconciled in November, signing the Riyadh Agreement and agreeing to form a blended government, with the STC also gaining a seat in peace negotiations. Such a government has yet to be formed, and at the end of 2019 the Yemeni government had no negotiating team to send to peace talks. In 2020, progress will be necessary on this aspect of the Riyadh Agreement for a formal peace process to begin. Going into 2020, the UN envoy’s office envisioned this could be achieved and peace negotiations could begin in March 2020.

The UN envoy remains committed to a framework that seeks the most reductive agreement possible to stop the war — an “end the war agreement” rather than a “peace agreement”. This approach seeks a swift agreement — without extraneous negotiations — on basic security and political arrangements, with major decisions on post-conflict Yemen deferred to the transitional period. Under this roadmap, wartime leaders would not be relied on to make decisions for peacetime. However, Griffiths’ detractors have criticized the limited scope of his vision and the deferral of complex details, and argue that critical issues such as the economy, which has been weaponized by both sides in the conflict, must be addressed in any peace agreement if it is to have any hope of success.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Yemen and the United Nations’ including:

Yemen and the United States

Away from tension in the Gulf and back in Washington, domestic legislative pressure on issues related to Yemen became less visible in 2019 following the escalation that began in late 2018 with the assassination of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. A bipartisan resolution to end US support for the Saudi-led coalition came to the end of the road in April with a presidential veto, yet arguably fulfilled its symbolic rather than legal aims. Other standalone bills taking aim at US involvement in Yemen and weapons sales to coalition member states saw little progress over the course of the year. Meanwhile, the US State Department said in late 2019 that it, along with the Pentagon, was investigating allegations made in CNN investigations that the Saudi- and Emirati-led coalition had passed on, sold or abandoned US-made weapons in Yemen. Such actions, CNN reported, may have violated arms export agreements.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Yemen and the United States’ including:

- Legislative Drive Fizzles as Yemen Slips Down the Agenda

- Reports Claim US Weapons Used by Non-State Actors in Yemen

Yemen and the European Union

European domestic debates about Yemen in 2019 largely focused on arms exports to the Saudi- and Emirati-led military coalition. Aside from attention in the media, among NGOs and in parliaments, European arms exports also triggered legal cases and diplomatic quarrels. By the end of the year, however, the uproar over arms sales to Saudi Arabia that was prompted by the Khashoggi affair had died down. Despite some individual countries still curtailing exports — by choice or legal challenge — broader European defense projects appeared back on track.

On the European diplomatic front, the first half of 2019 saw frequent visits by European officials to Yemen and the region to discuss the UN-led peace process, with Britain taking its usual front-running role in Yemen-related diplomacy. Besides Britain’s significant military-economic interests in the region generally, the former colonial power in southern Yemen is penholder of the Yemen file at the UN Security Council. A former British diplomat, Martin Griffiths, also leads the UN’s diplomatic efforts as the UN’s special envoy to Yemen. However, Boris Johnson’s assumption of the prime minister’s office in July came with an overriding focus on British domestic affairs. Britain’s new government, including its newly appointed foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, did not appear to share its predecessor’s interest or even knowledge in the Yemen file. Diplomatic rotation swept aside another diplomat, EU Ambassador Antonia Calvo-Puerta, who had developed a reputation for engaging with and hearing out all sides.

The second half of the year was overshadowed by broader regional tension with Iran, and the Europeans, especially Britain and France, focused on trying to ease the escalating Iran-US crisis in the wake of a series of security incidents. The slow-going international mediation efforts led by the UN in Yemen since 2015 and supported by European powers were essentially overtaken by initiatives from Riyadh, which abruptly changed course after its anti-Houthi military coalition imploded in August and its oil facilities came under attack in September.

For in-depth coverage and analysis, see full section ‘Yemen and the European Union’ including:

- Germany, France, UK: Diplomatic Quarrels and Legal Challenges

- Europe’s Mediation Role Diminishes in 2019

A watermelon vendor shows off his produce in the Old City of Sana’a, January 28, 2019 // Photo Credit: Doaa Sudam

A watermelon vendor shows off his produce in the Old City of Sana’a, January 28, 2019 // Photo Credit: Doaa Sudam

Contents

Coalition Collapse and Rebirth

- Khalid bin Salman Takes Saudi Lead on Yemen

- Shock UAE Drawdown Sets the Stage for Coalition Turmoil

- The Anti-Houthi Coalition Implodes

- The Road to the Riyadh Agreement

Saudis, Houthis Enter Talks as Drone Warfare Ups the Ante

- The Year of the Drones

- Aramco Attack Exposes Vulnerability of Saudi Economy, Cease-Fire Ensues

- The Saudi-Houthi Backchannel

- Deescalation Loses Momentum as Year Ends

Life Under the Houthis: A Descent into the Dark Ages

- Bringing Government and Security Apparatuses into the Houthi Fold

- Religious Indoctrination

- Continuing Crackdown on Dissent

Political Developments: Fragmentation and the Struggle for Legitimacy

- Competing Parliaments

- De Facto Federalism in Government-Held Areas: Marib and Hadramawt

- Taiz: A Showcase of Power Struggles and Shifting Alliances

- Al-Mahra and Socotra: Pushing Back Against Saudi and Emirati Influence

- Tariq Saleh’s Statelet by the Red Sea

- Most Important Anti-Houthi Ground Forces

- The Northern Front

- Al-Dhalea Front

- Jihadis and Counterterrorism

Economic Warfare: Government and Houthi Struggle for Control Deepens

- International Legitimacy vs. Domestic Market Dominance

- Fuel Impasse Leads to UN Special Envoy’s Mediation

- Battle for Control Over Yemeni Banks and Money Exchangers

- Yemeni Rial and Government Food Import Mechanism Under Threat

- The Struggle to Rejoin a Divided Central Bank

- Favoritism, Currency Shenanigans and Market Monopolies

- FSO SAFER Environmental Threat Rises

- Looking Beyond the Numbers

- Aid Interference Comes into Sharp Focus

- Human Rights: Seeking Accountability in the Yemen Conflict

- All Eyes on Iran

- Pakistan: Driving Mediation Efforts Between Iran and Saudi Arabia

- Oman: Between Mediation and Meddling

- Qatar: Undermining the Coalition

- Sudan: Scaling Down Troop Deployment in Yemen

- Morocco: Exiting the Coalition

- Legislative Drive Fizzles as Yemen Slips Down the Agenda

- Reports Claim US Weapons Used by Non-State Actors in Yemen

- Germany, France, UK: Diplomatic Quarrels and Legal Challenges

- Europe’s Mediation Role Diminishes in 2019

List of Acronyms

ACLED – Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

AP – The Associated Press

AQAP – Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

CAAT – The Campaign Against Arms Trade

CBY – Central Bank of Yemen

CENTCOM – United States Central Command

DGSI – France’s General Directorate for Internal Security

EU – European Union

GBV – Gender-Based Violence

GEE – UN Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen

GPC – General People’s Congress

HRW – Human Rights Watch

ICRC – International Committee of the Red Cross

IDP – Internally Displaced Person

INGO – International Non-Governmental Organization

IOM – International Organization of Migration

IS – The Islamic State Group

JIAT – Joint Incidents Assessment Team

LCs – Letters of Credit

MOPIC – Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation

MSF – Médecins Sans Frontières

NAMCHA – National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

NDAA – National Defense Authorization Act

NGO – Non-Governmental Organization

NSC – National Salvation Council

NYT – The New York Times

OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

OSESGY – Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen

RCC – Redeployment Coordination Committee

RSF – Reporters Sans Frontières

SCMCHA – Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation

SPC – Supreme Political Council

STC – Southern Transitional Council

UAE – United Arab Emirates

UAV – Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

UK – United Kingdom

UN – United Nations

UNHCR – United Nations Refugee Agency

UNICEF – United Nations Children’s Fund

UNMHA – United Nations Mission to support the Hudaydah Agreement

UNSC – United Nations Security Council

US – United States

WFP – World Food Programme

WHO – World Health Organization

WSJ – Wall Street Journal

YHRP – Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan

YJS- Yemeni Journalists Syndicate

YPC – Yemen Petroleum Company

YR – Yemeni Rial

Coalition Collapse and Rebirth

Khalid bin Salman Takes Saudi Lead on Yemen

Setting the context for the year, there was a significant shift regarding the Yemen file in Saudi Arabia in the early weeks of 2019, when Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s brother, Khalid bin Salman, was named deputy defense minister and handed responsibility for Yemen. He was a key force in pushing through the Riyadh Agreement (see ‘The Road to the Riyadh Agreement’), and in the Saudi-Houthi backchannel talks established in the autumn of 2019 (see ‘Saudis, Houthis Enter Talks as Drone Warfare Ups the Ante’).

With Khalid bin Salman’s appointment, there was a clear responsibility for the Yemen file for the first time in years. While Mohammed bin Salman is regarded as the architect of Riyadh’s 2015 Yemen intervention, the last prince fully overseeing Saudi Arabia’s relationship with its southern neighbor was longtime defense minister Sultan bin Abdulaziz, who died in 2011. Prince Sultan was known as being deeply familiar with the Yemeni context, maintaining a strong personal network and presiding over a special committee that bought loyalties through the disbursal of salaries to key political figures in Yemen and oversaw development projects in the country. The committee had been founded as a result of the North Yemen civil war of the 1960s, when Saudi Arabia supported the royalists against the republicans.

After Prince Sultan’s death, the Yemen file was transferred to the Ministry of Interior, where it was more or less adrift. This led to a vacuum regarding in-depth knowledge about and personal ties with stakeholders in Yemen, which has contributed to ill-founded assumptions and political failures in Riyadh’s Yemen policy. With the appointment of Khalid bin Salman, the Yemen file is back at the Ministry of Defense. According to a report by Foreign Policy, Prince Khalid was tasked with delivering a face-saving deal to extract Saudi Arabia from the Yemen War.[1]

Shock UAE Drawdown Sets the Stage for Coalition Turmoil

Throughout 2018, the UAE led the coalition campaign to capture Houthi-held Hudaydah city on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast, the entry point of most of the country’s commercial and humanitarian cargo and, consequently, a major revenue stream for the armed Houthi movement through the levying of import duties and fees. Emirati efforts included both heavy international lobbying efforts – particularly in the US – for diplomatic and military backing for the offensive, as well as arming, funding and coordinating between various armed groups on the ground to lead a military drive north up the coast. The Emirati argument had been that Hudaydah could be taken quickly with minimal interruption in the flow of goods through the area’s vital ports, and that the loss of the city and port revenues would pressure Houthi leaders to return to the negotiating table. Many UN agencies, INGOs, Western lawmakers and diplomats, among others, argued that Houthi fighters were well entrenched, the battle would be prolonged and the resultant disruption in imports would cast Yemen into mass famine.

As UAE-backed local forces fought their way to the city’s periphery in autumn 2018, coalition partner Saudi Arabia, and in particular Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, was coming under blistering international criticism for the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. This snowballed into criticism of the Saudi intervention in Yemen generally and the coalition attack on Hudaydah specifically. Leveraging this momentum – and international and UNSC backing – UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths was able to bring the Yemeni government and Houthi representatives to Sweden in December 2018 for peace talks. Seeking reprieve from international scorn, Bin Salman compelled the Yemeni government to accede to the UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement, which, among other things, froze the coalition assault on Hudaydah.

Diplomatic sources told the Sana’a Center that Emirati officials were furious their efforts to take Hudaydah had been undercut, and that the Stockholm Agreement prompted the UAE to reassess its role in Yemen. By June 2019, Abu Dhabi was undertaking a large-scale removal of military assets and personnel from the country in a move that injected further uncertainty in an already fractious anti-Houthi coalition. Emirati officials at the time characterized the redeployment as a “natural progression” from the 2018 Stockholm Agreement in comments to Reuters, with the news agency also quoting western diplomats who ascribed the move to the UAE wanting to shore up the homefront amid rising regional tension with Iran (see ‘UAE Reassesses Relations With Iran’).[2]

In July, a senior Emirati official claimed the drawdown had been coordinated with Saudi Arabia for more than a year and that the decision marked a shift from a “military-first” strategy to a “peace-first” plan. Coalition spokesman Colonel Turki al-Malki said the UAE and other coalition member states remained committed to the restoration of the Hadi government.[3] On August 2, the Emirati minister of state for foreign affairs, Anwar Gargash, said the UAE had “agreed with Saudi Arabia on the strategy of the next phase in Yemen.”[4]

Following a military drawdown across most of its areas of operations in southern Yemen, the UAE eventually completed a full withdrawal from Aden on October 30 and handed over security responsibility to Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni government. However, the General Command of the UAE Armed Forces stated that Emirati forces would continue the “war on terrorist organizations” in Yemen’s southern governorates.[5] As of the end of 2019, Sana’a Center research was able to confirm that the UAE had maintained a presence along the Red Sea Coast at Mokha, as well as along Yemen’s southern coast at Balhaf in Shabwa governorate and in Hadramawt at Mukalla port and Riyan airport.

From Military Expansionism to Withdrawal: Four Years of the UAE in Yemen

The rulers of Abu Dhabi have long seen their alliance with Riyadh as key to their country’s geostrategic security. The preservation of this alliance was their primary motivation in following Saudi Arabia into the Yemen War in 2015. The Saudi campaign was led by the then-29-year-old newly minted defense minister, Mohammed bin Salman, who essentially came under the wing of the elder Mohammed bin Zayed, crown prince of Abu Dhabi and head of the Emirati campaign in Yemen. The Emirati role also ensured that Abu Dhabi would have its own hand in guiding developments in Yemen.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE led and were by far the largest contributors to a regional military coalition that initially also included Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Sudan, Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar.[6] The general division of tasks had Riyadh taking responsibility for the air campaign and Abu Dhabi heading the ground war. The UAE was also the more active of the two on the international diplomatic front, lobbying at the UN and in Western capitals for support for the coalition campaign and keeping criticism at bay.

While quickly establishing a significant military presence of its own forces in Yemen’s southern governorates and Marib, Abu Dhabi’s calculus changed dramatically following an attack in Marib on September 4, 2015, which left 45 Emirati soldiers dead.[7] It was the deadliest single day for the Emirati military since the country’s founding in 1971. Following this the UAE pulled its troops away from the frontline and began investing heavily in recruiting, training, arming and financing numerous paramilitary groups in Yemen. Among these have been the Security Belt forces in Aden, “Elite Forces” in Shabwa and Hadramawt, the Abu al-Abbas Brigades in Taiz, the Giants Brigades, and since 2018 Tariq Saleh’s National Resistance Forces. The Emirates also became the primary backer of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Yemen when the southern secessionist group emerged in 2017.

Officially the UAE, as part of the regional coalition, entered Yemen to push back the Houthi advance and restore the Hadi government to power in Sana’a. Emirati actions on the ground, however, demonstrated that an array of other agendas were at play, and ones that seemingly undermined its stated intentions. Fostering paramilitary groups that operated outside the purview of the Yemeni government served a confluence of these Emirati aims. For instance, Abu Dhabi regards the regional Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization and often employed its Yemeni proxies against the brotherhood’s sister party in Yemen, Islah, even though the party constitutes President Hadi’s largest political and military support base in Yemen. The STC, whose founding principle is the reestablishment of South Yemen as a separate country, also regularly challenged the Yemeni government’s authority – a situation regarding which Abu Dhabi seemed wholly unconcerned. Additionally, the UAE used its proxies to secure coastal areas and ports along Yemen’s southern, and later western, shoreline, which can been seen as part of the Emirate’s larger regional strategy of asserting influence over crucial waterways for global trade, such as the Gulf of Aden, the Bab al-Mandeb Strait and the Red Sea. Local proxy forces also became the backbone of the UAE’s counterterrorism efforts against Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), through which Abu Dhabi continued to cement, through demonstrated dependability and effectiveness, its relations with the US military.

As international criticism of coalition actions in Yemen mounted, in particular indiscriminate Saudi airstrikes on civilian targets and accusations that the coalition was instigating famine in Yemen, the UAE found the image it has attempted to build for itself – that of a modern, progressive society – being tarnished. The Khashoggi murder, and subsequent Stockholm Agreement – which undermined more than a year of intense Emirati military and diplomatic efforts aimed at capturing Hudaydah – was the tipping point. Having demonstrated loyalty to Riyadh in entering the Yemen War, after four years the rulers of Abu Dhabi had enough.

The Emirates has already stated, however, that it will maintain a reduced troop presence in Yemen in the name of counterterrorism – with these forces also happening to be based at strategic ports along Yemen’s coast, and in the case of Balhaf, at a multi-billion dollar LNG export terminal owned by an international consortium led by France’s Total. It would thus appear that, moving ahead, Abu Dhabi does not intend to abandon its interests in Yemen. Rather, the troop drawdown was intended to reduce Emirati responsibility for, and limit its exposure regarding, the wider war with the Houthis.

The Anti-Houthi Coalition Implodes

After Aden Attacks, STC Stages Coup D’etat Against Yemeni Government

On the morning of August 1, Aden was hit with two mass-casualty attacks. In the first, an IS suicide bomber blew up an explosives-packed vehicle just outside the gates of the Sheikh Othman police station, killing 13 police officers.[8] Just an hour later, another explosion tore through a graduation ceremony at Al-Jalaa military camp, a base for the UAE-backed Security Belt forces. The armed Houthi movement later claimed it had attacked the camp with a drone and medium-range ballistic missile.[9] Video of the incident showed hundreds of soldiers marching in place before a loud explosion sent grey smoke billowing behind the stage and soldiers running. The attack killed 35 soldiers, according to interior ministry figures,[10] and a popular commander, Brig. Gen. Muneer al-Mashali, better known as Abu al-Yamama.

Abu al-Yamama first gained prominence fighting the Houthis during the 2015 Battle of Aden, and had an intensely loyal following in his native Lahj governorate, with many residents from his home district of Yafa joining Emirati-backed security forces. He was also an ardent southern separatist and his death sparked widespread rage among supporters. Anti-northerner sentiment spiked in Aden, with northern-owned businesses vandalized and northerners forcefully deported. Hani bin Breik, a militant Salafist and vice president of the STC, capitalized on the event by accusing the Yemeni government and Islah party of colluding with the Houthis to assassinate Abu al-Yamama, further inflaming public anger.[11]

On August 7, during Abu al-Yamana’s funeral, tension erupted into open violence between Security Belt forces and the government-affiliated President Protection Brigades, with Bin Breik then calling on STC-affiliated forces to march on the palace and overthrow “the pro-Islah government.”[12] Fighting spread through the city in the following days, with Security Belt forces seizing control of government buildings and military bases and the few ministers present in Aden at the time fleeing, including Interior Minister Ahmed al-Maysari, who had led the fighting on the government side. By August 10, after the surrender of pro-government forces at Ma’ashiq presidential palace, the STC was in full control of the city.[13] The fighting left up to 40 people dead and 260 injured, according to the UN humanitarian coordinator’s office.[14]

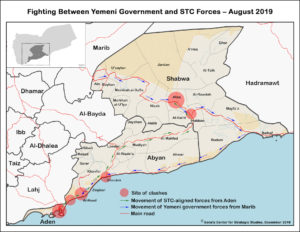

Bolstered by their victory over the Yemeni government in Aden, STC-aligned forces quickly moved to seize other areas across southern Yemen. Security Belt forces captured government military bases in neighboring Abyan governorate on August 19,[15] and on August 22, fighting broke out in Ataq, the capital of Shabwa governorate, with fighters from the UAE-backed Shabwa Elite Forces squaring off against the pro-government 21st Mechanized Brigade.[16] However, government troops in Abyan, the home governorate of President Hadi, mobilized to cut off STC-aligned reinforcements being sent from Al-Dhalea and from Yafa in Lahj, while prominent Shabwa tribes – including some members of the Shabwa Elite Forces – declined to join the fight against government forces. The STC advance thus hit a wall.

On August 25, coalition spokesperson Turki al-Maliki announced the creation of a joint committee to supervise a cease-fire in Shabwa. Government forces then took over Shabwa Elite positions, including its headquarters in Balhaf.[17] STC-aligned forces, pushed out of all of Shabwa, were then forced to contend with Yemeni government troops marching on Aden toward the city’s airport and eastern suburbs.[18] On August 29, Emirati warplanes launched airstrikes against pro-Hadi forces to protect its STC allies, killing at least 30 troops and prompting the Yemeni government to seek Saudi action and UN Security Council intervention against the UAE.[19] [20] By the end of August, the STC controlled Aden, the government held Shabwa, and Abyan was split between the two.

Separatist Ambitions Hit Southern Reality: How the STC was Humbled

The STC defeat in Shabwa was a reality check for the group. It was founded on the vision that South Yemen, united and autonomous, could be carved out once again from the larger republic, and that the STC, as the representative of all southern interests, was the group that could make this happen. The loss in Shabwa revealed this vision to be fanciful. Chiefly what was made apparent was that southern Yemen was far from united and that the STC, rather than being a great unifier of a greater cause, was another one of many localized stakeholders in the Yemeni conflict with limited influence. While southerners may still widely share an animosity against the north, the events of 2019 showed that this was not a sufficient condition to bridge the divides among them.

Collective southern grievances with the north originated from the concentration of power in Sana’a following the 1990 unification of Yemen. The south’s defeat in the north-south civil war in 1994 and southerners’ subsequent marginalization only reinforced the sense that they were victims of injustice. The central government’s violent suppression of protest movements in the south beginning in 2007 gave birth to the Southern Movement (commonly known as Hirak), a loose umbrella organization encompassing various pro-separatist groups.

In 2017, Aidarous al-Zubaidi formed the STC after Hadi dismissed him as governor of Aden over his support for the Southern Movement. The STC gradually established de facto security control over Aden through the Security Belt forces and formed a would-be southern parliament, the National Assembly. The August 2019 events were not the first time the STC had flexed its muscles in Aden; in January 2018, STC-aligned forces took control of the government’s headquarters in the interim capital and briefly kept ministers under house arrest. Saudi and Emirati mediation brought the hostilities to an end but the wheels had been firmly set in motion; since then, the STC has effectively dominated the city. From this base of strength, the STC has projected for itself the image of representing all southerners. The events in August laid bare how tenuous this claim was and how the Southern Movement was internally fractured.

Old divisions from South Yemen’s own civil war in 1986 between Lahj and Al-Dhalea on one hand, and Abyan and Shabwa on the other, became apparent when the STC’s expansion into the latter two governorates was met with faltering local support. Abyan and Shabwa have historically benefited through cooperation with the ruling regimes of the time, first during British occupation and later in the united Yemeni republic, which saw many members of the security forces, including top officials, recruited from these two governorates. Lahj and Al-Dhalea on the other hand, where STC-affiliated units mainly recruit, were historically more marginalized and thus tended to stand in opposition to ruling authorities. President Hadi has also been able to secure a base of loyalty in his home governorate of Abyan through military and government appointments, which helped counter the STC expansion there.

In Shabwa, the STC is allied with UAE-backed Shabwa Elite Forces, and yet tribal dynamics also played against the STC’s advance. The UAE had recruited members into the Elite Forces along tribal lines. This strategy harmed overall cohesion as each tribe had its own calculations related to the government-STC split, and a significant part of the Shabwa Elite Forces chose not to fight with the STC. Most importantly, influential Sheikh Saleh bin Fareed al-Awlaki refused to support the STC in its battle against the Hadi government.

Fears over being cut off from neighboring Marib, a stronghold for the government-allied Islah party, likely also played into the decision of Shabwa tribes. Marib and Shabwa share cultural, linguistic and tribal similarities, and also economic interests. Shabwa relies on liquefied petroleum gas produced from Marib, and there have been talks about exporting Marib crude via Shabwa.[21] Furthermore, Saudi Arabia maintains historical ties with tribes from Shabwa. When government troops advanced into Shabwa from Marib to counter the STC advance, tribes allied with the government stayed neutral and refused to support the STC. Thus humbled and their ambitions for southern Yemen shown to be beyond them, STC leaders were seized with a new pragmatism when Saudi Arabia launched efforts to reconcile division in the anti-Houthi side.

For more, see the Sana’a Center’s analysis of developments in the south from the August monthly review.[22]

The Road to the Riyadh Agreement

Saudis Bring Rival Parties Together for Talks

Riyadh’s reaction to the violence in Aden was to attempt to halt the fighting and start peace negotiations between the STC and Yemeni government. To facilitate this, Riyadh first had to address its rift with Abu Dhabi that had become apparent in the latter’s military drawdown in Yemen. Saudi King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman met on August 12 with Emirati Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan in Mecca, after which the leaders reiterated calls for the Yemeni factions to resolve their differences through dialogue.[23] Despite the public unity, Reuters news agency reported that the Saudi ruler had taken the unusual step of expressing his “extreme irritation” with the UAE during the Mecca meeting.[24]

Initially, the Yemeni government said it would not begin any talks without a complete STC withdrawal from areas it had seized in August. Both parties eventually agreed to take part in negotiations in Jeddah despite continuing clashes, and an STC delegation, led by council head Aiderous al-Zubaidi, arrived in Jeddah on September 4.[25] Abdel Rahman al-Sheikh, a leading figure in the Security Belt forces who was pivotal in the STC’s victory in Aden, and Nasser al-Khabji, a longtime southern secessionist leader, were also among the delegation.

On September 9, Saudi Arabia and the UAE issued a joint statement in which they welcomed the response of the Yemeni government and the STC to the proposed negotiations, labeling it “a major and positive step” toward resolving the current tension in southern Yemen, and calling for an immediate end to all armed confrontations.[26] The STC responded to the statement by expressing its readiness to attend the talks in Jeddah without preconditions.[27] Meanwhile, President Hadi rejected the notion of any deal and reiterated the August demand that STC-aligned forces withdraw from all military bases seized during the fighting as a precondition to any dialogue.[28] A breakthrough between Saudi Arabia and the UAE appeared to come following an October 6 meeting between Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed and Khalid bin Salman, the Saudi deputy defense minister.[29] After this meeting, pressure was brought to bear on both sides and talks continued throughout October, culminating in the signing of the Riyadh Agreement in early November.

Deal Inked For STC to be Blended into the Yemeni Government, Security Forces

On November 5, the internationally backed Yemeni government and the STC signed the Riyadh Agreement to end their power struggle in southern Yemen.[30] As part of the deal,[31] the STC would be given an official role in a reshuffled Yemeni cabinet of political technocrats and at future peace talks to end the larger Yemen conflict. In exchange, all STC-aligned military and security forces would be blended into units under the authority of the government’s Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior, respectively. The agreement also called for the return of the Yemeni government to its interim capital of Aden and for reactivating all Yemeni government institutions. Although brokered during weeks of talks in Jeddah, the accord was signed in Riyadh during a ceremony attended by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, Yemeni President Hadi and STC leader Al-Zubaidi. The actual signing was done by Yemeni government Deputy Prime Minister Salem al-Khanbashi and Aden’s former governor and STC member, Nasser al-Khabji.

While the agreement calls for reactivating the Yemeni government and giving the ministries of defense and interior full purview over the unified military and security forces, in the end all of these institutions remained directly answerable to a Saudi-run committee. As undisputed lead actor in the anti-Houthi coalition, Saudi Arabia would assume command responsibilities previously held by the UAE, security responsibility for Aden and other southern governorates, and overall authority over the integrated military and security forces of the anti-Houthi coalition. Saudi military reinforcements began entering Aden and other southern governorates in October to take over positions from withdrawing Emirati forces. The transition from Emirati to Saudi patronage also egan occurring for formerly UAE-backed groups in southern Yemen, a process that was not without growing pains. One Security Belt forces member who spoke to the Sana’a Center complained about the Saudis being less generous than Emiratis, highlighting that the military kitchen hadn’t provided dessert since the Saudis’ takeover.

Along with a timeline for securing Aden and reactivating the government in the interim capital, the Riyadh Agreement also contained several clauses aimed at improving government efficiency and transparency. All state revenues were to be deposited in the central bank in Aden, which would end the growing practice, in some governorates nominally under government control, of local administrations collecting and spending what legally are state revenues. The mention of reactivating parliament’s oversight role and supervisory agencies such as the Supreme National Anti-Corruption Commission and the Central Organization for Control and Auditing implied a Saudi-backed push to root out graft and corruption. However, without initiatives to address high-level corruption, including patronage appointments made by Hadi, any improvement in accountability in Yemeni governance would likely be partial and piecemeal at best.

For more on the Riyadh Agreement, see the Sana’a Center’s analysis of the accord.[32]

Stalled Implementation and Missed Deadlines

The lofty goals laid out in the Riyadh Agreement also included an ambitious timeline, and between the signing of the agreement and the end of 2019 every implementation deadline had been missed. While there was progress on some aspects of the agreement, most saw little movement. On November 18, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed arrived at Aden airport, six days later than the stipulated November 12 return of the government to the interim capital and reactivation of all state institutions in areas outside Houthi control. The return of the PM would be the only benchmark in the entire Riyadh Agreement reached by the end of the year.

On the political front, other deadlines passed unheeded in November and December, including the appointment of a new governor and security director for Aden governorate, new governors for Abyan and Al-Dhalea governorates and, in the first missed deadline of 2020, the planned appointments by January 4 of governors and security directors in all remaining southern governorates.

Sensitive military aspects of the agreement also failed to materialize on schedule, most notably the redeployment of Yemeni government and STC-aligned forces from areas they moved into in Aden, Abyan and Shabwa governorates to their pre-August positions, and their replacement with security forces from the relevant local authorities. These and other measures on the military front failed to materialize by their December 5 deadline, including the redeployment of all government and STC military forces in Aden to camps outside the governorate – except for the 1st Presidential Protection Brigade charged with securing the Ma’ashiq presidential palace – and the transfer of medium and heavy weapons in Aden to camps in the city under Saudi supervision.

On the security front, the missed December 5 deadline also included local police assuming responsibility for security in Aden governorate; and the reorganization of special forces and counterterrorism forces in Aden, and of forces responsible for the protection of government facilities, as well as their placement under the control of the Ministry of Interior. By January 4, all military and security forces across southern Yemen were supposed to be assigned, unified and placed under the authority of the Ministry of Defense or Ministry of Interior.

As 2019 came to a close, there was little indication that either the Yemeni government or the STC was genuinely committed to the union both sides signed onto in Riyadh. On the first day of the new year, the STC announced that it was suspending participation in joint committees intended to implement aspects of the accord, citing a minor flareup in violence in Shabwa governorate that it blamed on the Islah party.[33] However, even before the STC move, the committees were doing very little to achieve their stated purpose of ironing out contentious details ahead of forming a unified political and military front. Government and STC officials confirmed to the Sana’a Center that both parties have generally refused to negotiate with each other, preferring instead to meet with Saudi emissaries.

If the Hadi government and the STC did come together as a single governing entity as envisioned in the Riyadh Agreement, the united front under Saudi direction would be far better placed to escalate pressure on the Houthis politically, militarily and economically. This, in turn, could provide the anti-Houthi coalition additional leverage at the negotiating table, as a weakened Houthi position may make the armed movement’s leaders more amenable to concessions which they currently see no need to make. A unified anti-Houthi front would also be a reversal of the recurring cycles of fragmentation the country has experienced since the 2011 Yemeni uprising. Even the partial success of the Riyadh Agreement remains an optimistic prospect, however, given the lack of movement since the signing of the deal.

A member of the Security Belt forces stands on a vehicle during a military ceremony in Aden. Shortly after, dozens were killed in an attack on the base, August 1, 2019 // Photo Credit: Rajeh Al-O’mary

A member of the Security Belt forces stands on a vehicle during a military ceremony in Aden. Shortly after, dozens were killed in an attack on the base, August 1, 2019 // Photo Credit: Rajeh Al-O’mary

Saudis, Houthis Enter Talks as Drone Warfare Ups the Ante

The Year of the Drones

On January 10, 2019, Houthi forces targeted a military parade at Al-Anad air base in Yemen’s Lahj governorate with a bomb-laden drone, killing, among others, the Yemeni government’s military intelligence chief, General Mohammed Tamah, and the army’s deputy chief of staff, Saleh al-Zindani.[34] Shortly after, Houthi military spokesperson Yahya Sarea declared that 2019 would be “the year of the drones.” This proved to be an apt characterization.

Despite coalition attempts to destroy alleged Houthi drone storage facilities later that month, Houthi drone and missile attacks would continue to ramp up in the months that followed. For instance, in April, Saudi air defenses positioned around Sayoun, in Hadramawt governorate, shot down almost a dozen drones the evening prior to a parliamentary session being held in the city.

Mid-May to September witnessed a steady stream of Houthi aerial attacks against military, commercial and civilian infrastructure in Saudi Arabia. On May 14, Houthi forces employed drones to target oil pumping stations for a Saudi Aramco pipeline near Riyadh. Houthi chief spokesperson Mohammed Abdel Salam said the attack marked a “new phase of economic deterrence” in response to the coalition’s intervention in Yemen.[35] Senior Houthi leader Mohammed Ali al-Houthi said his forces had stepped up cross-border attacks – including strikes later in May against Jizan airport in southern Saudi Arabia – after the Saudi-led military coalition had spurned “peace initiatives” by the movement.[36] In the months that followed, Houthi forces continued to launch missiles and armed drones at targets in southern Saudi Arabia, including Jizan and Abha airports and King Khalid Air Base near Khamis Mushait. In August, an aerial attack targeted Shaybah oilfield near Saudi Arabia’s eastern border with the UAE.

The Houthi movement publicly showed off some of its new weapons capabilities in July at an exhibition in Sana’a, including long-range combat and surveillance drones, as well as ballistic and cruise missiles. Among them was the latest incarnation of the Samad drone, which the Houthis claim has a range of 1,700 kilometers and said was used in attacks on airports in Saudi Arabia. Houthi forces spokesperson Yahya Sarea said that the weapons were made in Yemen and were the product of domestic innovation.[37] However, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen had previously concluded in its 2018 report that certain models of drones in the Houthi arsenal or their components originated from Iran.[38]